This is the second in a series of posts exploring how historians can engage with AI tools. Please subscribe if you want to receive the next posts. If you're a historian dealing with similar questions, I'd like to hear about your experiences.

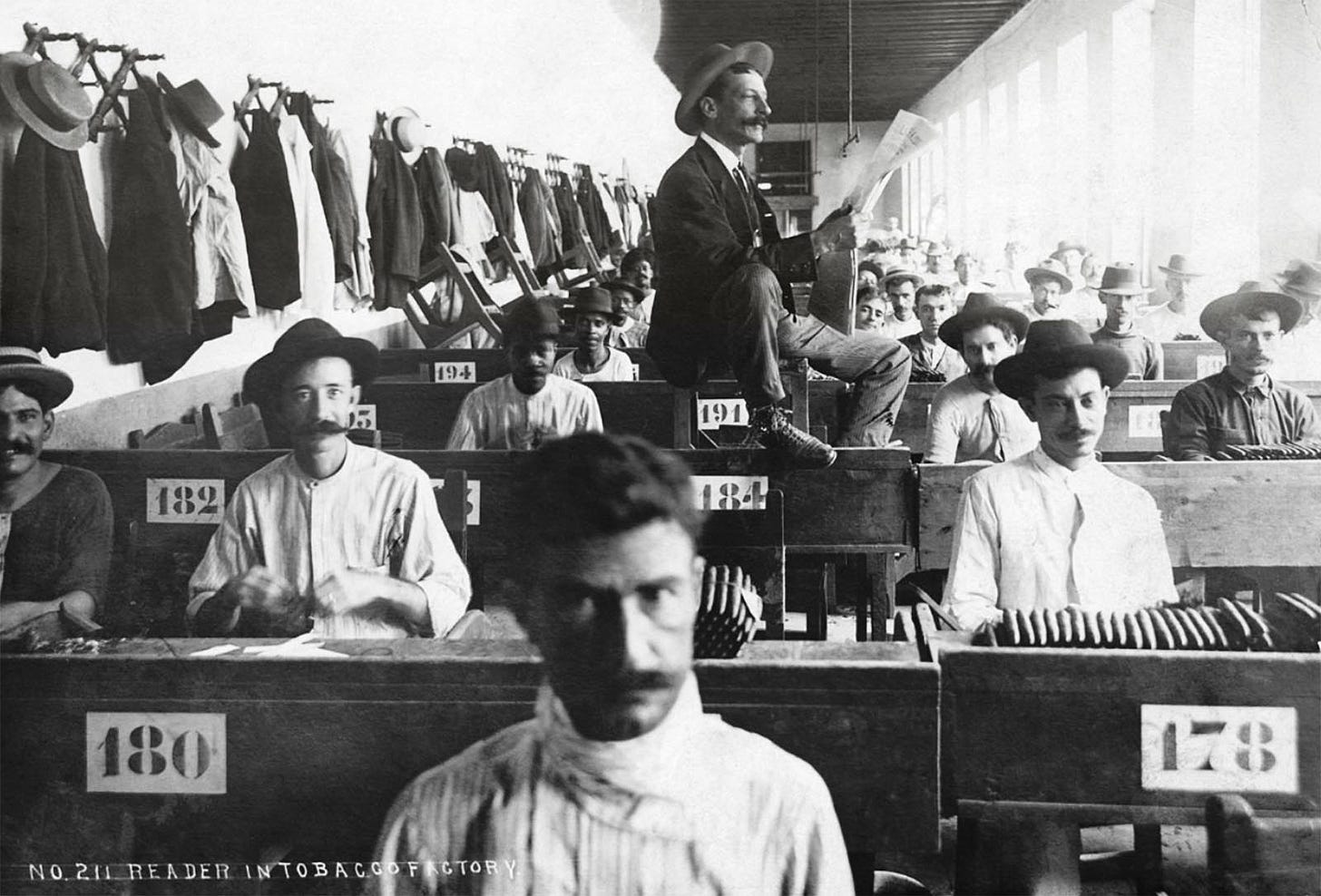

Image: A “reader” reading aloud to workers engaged in manual labour in a Cuban cigar-making factory, ca. 1900.

Discussions about generative AI in higher education, particularly in the humanities, are fixated on how AI can generate essays and research papers. The dominant fear is that students will stop writing, but the real danger, an insight I owe to a perceptive colleague, might be that they will stop reading.

Indeed, we should think and discuss collectively about what might be the most revolutionary (or counter-revolutionary) change of the age of generative AI, at least for us: the possibility to “read” so many things without actually reading them.

I’m not talking about the standard versions of chatbots like ChatGPT, Gemini or Claude. Ask them for the main argument of The Little Prince and probably they will get it right (I didn’t try). But ask about a less known academic monograph in history, and you will get vague yet plausible generalizations and, after a bit of pushing, direct hallucinations. (True, these chatbots can also be used with your own uploaded sources, but don’t trust that too much either. When the PDF you upload is too large, the tool will simply read a part from it and ignore the rest, especially if you don’t have a premium account, and give answers based only on that, without letting you know.)

I’m focusing here on RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) tools, like NotebookLM, the ones that provide answers only based on the sources you upload. Unlike general-purpose chatbots that draw from their vast but fixed training data, RAG systems work with your specific documents. When you upload sources, the system breaks them into searchable chunks and creates an indexed knowledge base. When you ask a question, it retrieves the most relevant passages from your documents, then uses those excerpts to generate its response. In the answer, the tool provides direct quotations and citations from your sources. It is like having a conversation with your archive, not with the entire internet.

Do a little experiment. Go to notebooklm.google.com, log in with your Gmail credentials, create a new “notebook”, and upload a PDF of an academic work you know very well. If possible, something you have written yourself. After you have uploaded it, start asking all sorts of questions about the text. Go from a general “What is the main argument of this text?” to much more specific queries, like what are the arguments of each chapter, what is the methodology and underpinning theory, how the author positions themselves in the historiographical field, what are the main inconsistencies and weak points in the argument, etc.

The result, as you will quickly see, is a very solid review of a given book, ready in a matter of minutes. Not a brilliant one, to be sure, because the tool is missing additional context, knowledge about the field, and other sources that a specialist will know. But still a very good one. You can take it a step further. Upload a dozen more sources on the same topic in the same “notebook”, and ask things like “What are the methodological disagreements between these historians?” or “Which of these authors would agree with each other about causation?”. Try different questions, different prompts, iterate, insist, ask for deeper connections.

***

There are reasons for enthusiasm. Literature reviews that once took months can now be drafted in hours. The system can spot patterns across sources better that we could possibly do. Even more fascinating: it allows us to work with texts in unfamiliar languages and find connections across dozens of works simultaneously. In other words: it feels as if research capabilities once limited to a handful of professors at elite universities with large teams of research assistants are now accessible to anyone who knows which sources to collect and what questions to ask.

Alas, the losses are also profound. All this might be a true blessing if your reading assignment was a tedious 50-page corporate marketing paper (probably also written with AI), but this shortcut becomes a trap in the humanities. Even if you get the main idea of a book or chapter in a quite adequate way, you lose the discovery of a random footnote that opens up a new world of inquiry, the deep understanding of how scholars build arguments that comes only from practice, the historiographical sensitivity and the grasp of how debates evolved over decades, even the “feel” of different voices and the ability to recognize Hobsbawm or Thompson or Scott from their style alone. When we read a difficult text, we are constantly struggling with difficult passages, tracking complex arguments, and holding multiple threads in our memory to see how they connect. Not to mention the very pleasure of reading books, which is probably the reason we chose this job in the first place.

***

If we think more specifically about teaching in higher education, all this creates an existential pedagogical crisis. If NotebookLM can extract key arguments, methodological approaches, and evidence better than most students (and sometimes faculty), what does “reading” even mean anymore? If students can upload 20 secondary sources and ask “What are the main debates about the French Revolution’s causes?” and get a sophisticated and appropriate answer, what exactly are we going to teach them to do?

Traditional justifications for reading (“you need to read to understand the argument”) collapse when AI can extract arguments so reliably. Students, as anyone else, can and will understand the main points of a text without reading it. We find ourselves in the uncomfortable position of defending an intellectual process that AI can apparently replicate, or even improve.

***

What to do? I think it is useless to ban these tools. When you open a PDF in some versions of Adobe Acrobat, it already offers an AI-generated summary, and the same happens with PDFs opened in Chrome. This is everywhere, and it’s not going to disappear.

Perhaps what’s most important is to talk frankly with our students about this. Another insightful colleague who reacted to my previous post called this the risk of “outsourcing our cognitive skills”. NotebookLM presents a clean, comprehensible summary that bypasses the productive struggle of understanding. The problem is that the intellectual difficulty of reading complex academic texts builds analytical muscle. Students who never develop these muscles might become just consumers of knowledge rather than knowledge creators. They will be able work with AI summaries, ask good follow-up questions, even synthesize across sources, but they may never develop the deep reading skills that let them grapple with original or difficult ideas. I’m convinced that students not only understand these risks, but also share our concerns.

Moreover, we need to become experts in these tools ourselves. There is no other way to understand what they can and can’t do. Despite their power, RAG systems miss subtle shifts in tone and argument. They excel at answering questions but are poor at generating new ones. They have serious trouble identifying what hasn’t been said. They read the lines, but they struggle to read between them, missing the cultural assumptions and unspoken knowledge that an experienced historian recognizes.

Another crucial task is to adapt our teaching and assessment practices. We should still devise ways to ensure that students —at least in some courses— read directly from the books (paper copies if possible). And we should focus our assignments, conversations, and assessments on what AI can’t do: original interpretation, creative synthesis, original questions, and reading against the grain.

Me gusta mucho tu texto, Lucas. Justamente estamos hablando mucho sobre este tema y sobre la importancia de aprender a usar la herramienta que ha venido para quedarse. Creo que encontrás varios puntos en lo negativo, junto con la dificultad que tenemos de transmitir a generaciones que han nacido ya con herramientas digitales cuales son los riesgos o las debilidades. Congrats